Religion, Custom and Colonialism

For African women, asserting control over their bodies is a major challenge, with abortion one of the most contested areas related to their sexual and reproductive lives. While abortion should be considered a simple public health issue in the political realm, it is mostly seen through a cultural, moral or religious lens, which means the severe consequences of restrictive abortion laws on the lives and health of women are often not addressed. There is a general lack of consensus about the beginning of life based upon religion and custom. Because of antiabortion legislation dating from the colonial era, African women who decide to abort continue to pay a heavy toll in terms of mortality and morbidity. This article aims to analyze some of the social, legal and religious—specifically Muslim—aspects of the abortion debate. It focuses especially on the Francophone countries of West Africa, which form a geographical unit that was occupied in precolonial times by powerful empires (those of Mali and Ghana, for example), and which share the same cultural heritage, the same experience of French colonization and where Islamization dates back to the 11th century in some countries.

Except for Mauritania, all countries in West Africa are secular republics, but in every country, Islam and customary norms weigh heavily on family law and the status of women. For instance, sharia, a type of Islamic law, was adopted into the secular legal system in parts of Nigeria and Mali, while in Sierra Leone, Islamic law is only recognized for Muslims in certain circumstances, including questions of marriage and divorce. These norms also come into play when governments seek to legislate for the promotion of women’s rights or when attempts are made to implement international and regional instruments on women’s rights. However, religious and cultural precedents are wielded to the greatest effect when governments try to craft laws that would make any change in power relations within the private sphere. This includes provisions aiming to give women and girls more control over their bodies; greater freedom of choice of which person to marry; protection against violence, especially marital rape; and access to family planning or abortion. National policies related to these or any other women’s rights are still strongly and negatively influenced by interpretations of religious and cultural norms that are unfriendly to women. This trend is even more worrisome today with the recent surge of Islamic extremism in the region, including in its jihadist form. (For example, the occupation of Northern Mali by the group known as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.)

The Stubborn Reality of Unsafe Abortion

In 2003, the African Union drafted the Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa. Article 14, which pertains to health and reproductive rights (see p. 38), reads: “States Parties shall ensure that the right to health of women, including sexual and reproductive health is respected and promoted. This includes among others: the right to control their fertility; and the protection of the reproductive rights of women by authorizing medical abortion in cases of sexual assault, rape, incest, and where the continued pregnancy endangers the mental and physical health of the mother or the life of the mother or the fetus.” In 2007, the African Union drafted the Plan of Action on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights for 2007–2010, also known as the Maputo Plan of Action, which has nine areas of action, one of which is the reduction of the incidence of unsafe abortion.

But these principles have not trickled down to abortion availability for women; according to World Health Organization data from 2011, the unsafe abortion rate in West Africa is 28 percent among women aged 15–44, and for the same women, maternal mortality due to unsafe abortion is 12 percent.

On paper, most governments are committed to reducing unsafe abortion. Except for Mauritania and Niger, all 17 West African countries signed and ratified these regional documents. Four of those countries (Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso and Benin) allow abortion on some of the grounds indicated in the African Union’s instruments. The others, such as Senegal, still prohibit abortion except when a woman’s life is at risk—not based on sharia law, as is the case for Mauritania, but based on a French law prohibiting propaganda on contraception and abortion that dates back to the 1920s. This law was enacted after World War I by a right-wing regime to encour–age population growth. At that time, West African countries such as Senegal were still French colonies, but they did not repeal the law even after gaining their independence.

In these countries abortion is still a crime, but therapeutic abortion is permitted by the Code of Medical Ethics. In Senegal, for example, induced abortion, though not explicitly defined in the Penal Code, is punishable by imprisonment and fines. Article 305 of the code reads: “Whosoever, by food, drink, medicine, violence, or by any other means, provokes an abortion in a pregnant woman, whether or not with her consent, will be punished with a prison sentence of one to five years and a fine of 20,000 to 100,000 CFA francs [around $40–200 USD]. The woman who induces her own abortion, or who has consented to the use of means administered for that purpose, will be punished with a prison sentence of six months to two years” and a similar fine.

Although induced abortion remains unlawful, services are available for postabortion emergency care.

Islamic Positions About Abortion: No Consensus

This article focuses on Islam because the majority of people in West Africa are Muslim and Islam affects non-Muslims, as mentioned earlier in the examples of sharia adopted as civil law. Islamic religious leaders in West Africa condemn abortion, but when viewed in their totality, a dominant feature of Islamic teachings is that there is no consensus about the morality of abortion. The Solidarity Network of Women Living under Muslim Laws (WLUML) has been among the first to highlight the “myth of an homogenous ‘Muslim world,’” stating that “a) laws said to be Muslim vary from one context to another and b) the laws that determine our lives are from diverse sources: religious, customary, colonial and secular.” The lack of a Muslim consensus on abortion stems from the multiplicity of sources, which include the four canonical schools of law (Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi and Hanbali) and many modern thinkers. Each of the four schools has its own approach to abortion.

A review of chapters (Surah) of the Qur’an, or of the Sunnah of the Prophet Muhammad, brings the striking revelation that there are no precise directions pertaining to abortion. There is, however, great emphasis placed upon infanticide, which concerns already-born babies. With respect to abortion, the debate in both canonical and non-canonical sources centers on the beginning of life, which is invariably linked to the moment when the soul enters the fetus.

The Qur’an and the Hadiths (sayings) of the Prophet Muhammad give clearer insight into the phases of fetal growth, which are indicated to be seven, the seventh being the moment when the fetus receives its soul (ensoulment). The Qur’an states:

“We created man from an essence of clay: then placed him, a living germ, in a secure enclosure. The germ We made a leech; and the leech a lump of Flesh; and this We fashioned into bones, then clothed the bones with flesh. Then We develop it into another creation (Surah Al-Mu’minoon, 23: 12-14).”

An assumed authentic Hadith from the Prophet Muhammad says that a human being starts when a fertilized ovum has been in the uterus of the mother for 40 days. Then it grows into a clot for the same period; then into a morsel of flesh for the same period; then an angel is sent to that fetus to blow the soul (Ruh) into it and to write down its age, deeds, sustenance and whether it is destined to be happy or sad.

From other sacred sources, it is understood that ensoulment only happens after 120 days, and abortion is allowed before this period. But, because of the lack of consensus between the four canonical schools of law about the moment when the soul is breathed in the fetus, the canonical schools and related religious leaders dominant in each country may allow abortion with restrictions or forbid it. For example, since 1965, abortion is allowed in Tunisia up to the end of the third month of pregnancy. It is performed by trained doctors in healthcare settings for married as well as unmarried women. In West African Francophone countries where abortion is forbidden, this is due to the influence of the Maliki school of thought, which is the most conservative and forbids abortion, as well as the influence of the 1920 French law discussed above.

In addition, ensoulment is not the only consideration in Islam’s ethics about abortion. Sharia also allows abortion in some other cases, such as when doctors declare with reasonable certainty that the continuation of pregnancy will endanger a woman’s life. This permission is based on the principle of the lesser of the two evils, known in Islamic legal terminology as the principle of al-ahamm wa ‘l-muhimm (the more important and the less important).

The African Women’s Movement and Abortion

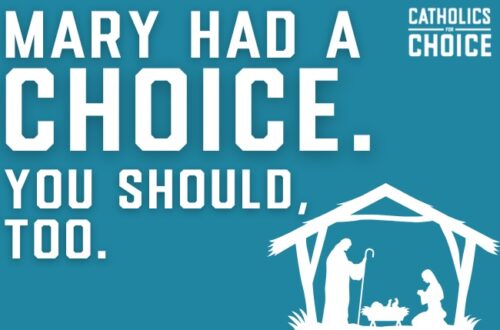

The right to safe and legal abortion, or other rights such as the right to express one’s sexual orientation, are not central to the West African women’s movement’s platform, except for individual women who embrace feminism or who are members of groups like the African Feminist Forum. For this group of women, access to free and medicalized abortion is a political issue: it’s about refusing the religious and customary rule that a woman’s life is worthy only if she is a mother. It is also a statement that sex for pleasure is as much a women’s right as a man’s right. It’s about a radical change in power and class relations, as wealthy women have the means to get an abortion in the best clinics and are protected by their class status. Expressing these opinions publicly exposes one to stigma, or to being considered brainwashed by Western feminists. This stigmatization may come from Muslims, from Christians—most of whom are Catholic and follow the Vatican’s position on sexuality—or from proponents of traditions that are pronatalist.

The material conditions in which the majority of African women live are characterized by low social status, deep poverty, lack of education and poor basic living conditions (limited access to water, to income-generating activities, to land, healthcare services, education about the law or the means to defend oneself). Given those conditions, the majority of women’s organizations choose to work to improve other facets of their sisters’ lives. Those who are active implementing women’s sexual rights usually fight for access to family planning or to put an end to violence against women.

Presently, in addition to prochoice feminists, there is an important lobby made up of female lawyers’ organizations working towards reforming abortion laws. They hold workshops with high-ranking officials of the health ministry, members of parliament and gynecologists, as well as religious and cultural leaders. These efforts have achieved little, as they only target the law, and legal reform alone does not necessarily change conservative opinions about an issue as sensitive as abortion. Additionally, the majority of African women are uneducated and often unaware that there are laws passed to defend their rights, among which may be the right to abortion.

Another point worth raising is the scarcity in Africa of funds needed to implement activities aiming at changing women’s social conditions and status. Most governments do not fund women’s organizations active in civil society. Ruling parties may, however, provide funds to their women’s wing.

Therefore the large majority of African women’s organizations, like all NGOs, are dependent on donors to get funds, which unfortunately forces them to depend on the donors’ agenda. Donors, whether they are United Nations agencies, aid agencies or international NGOs, all have their own agendas that may or may not coincide with the needs of African women. In that case, the African women’s organization usually complies with the donor’s mission because this granting agency is their only source of funds. As far as sexual rights are concerned, donors may fund activities related to family planning, HIV & AIDS, opposing violence against women, but in some cases avoid programs related to abortion. The situation was worse between 2001 and 2009, when US President George W. Bush’s administration withdrew funding for US international organizations that were partners of African associations that spoke, advised or educated about abortion or lobbied for the reform of abortion laws. Sadly, these strictures are still prevalent.

Old and New Methods of Control

Unsafe abortion claims the lives of many African women every day. This raises related issues, such as unintended pregnancies, access to family planning and the right to safe sex and to ownership over one’s body. Furthermore, -Africa’s ongoing problem with abortion accessibility and safety reveals the extent to which women’s bodies are the battlefield of old and new ways to control women—especially their reproductive functions and their sexuality. All over the world, women resisted and still resist this oppression, especially when it is in the name of religion or custom. African women take part in this struggle within alliances they built at the regional and international levels to demand equality and the promotion and protection of their rights. At the national level, they fight for the repeal of laws against abortion. Unfortunately, an absence of political will and increased pressure on Muslim populations, including women, to embrace a narrower Islamic view of abortion have so far impeded their struggle. For these reasons, women living in West Africa will continue the fight for the legalization of abortion as part of the global effort to expand sexual and reproductive choices.